This is the next in my Eugene/Architecture/Alphabet series

of blog posts, the focus of each being a landmark building here in Eugene. Many

of these will be familiar to most who live here but there are likely to be a

few buildings that are less so. My selection criteria for each will be

threefold:

Quackenbush Building

Located at 160 E. Broadway in downtown Eugene, the Quackenbush Building stands as an all too rare surviving example of the city’s early 20th century commercial architecture.

J. W. Quackenbush opened his

hardware store in the building soon after its construction in 1902. Initially,

the establishment primarily catered to the agricultural community, offering

farm implements, hardware, and horse-drawn vehicles. By the 1930s and 1940s,

the store diversified its offerings, emphasizing dinnerware and gift items as

hardware sales declined. Quackenbush’s uniqueness lay not just in its products

but in the personalized service it offered, a stark contrast to the rise of

impersonal discount stores. Despite challenges in the face of big-box retailers

and shopping centers, it remained a community institution, known for its family

atmosphere and traditional charm. It was a beloved fixture in the community right

up until its closure in 1980, holding the distinction of being Eugene’s

longest-running family business in a single location.

Since the store’s closing, the

building—still associated with the Quackenbush name—has been home to a

succession of businesses. Today, its tenants include J. Michaels Books, Porterhouse Clothing & Supply, Sterner Stuff, ArtCity Studios on Broadway, and Cameron McCarthy

Landscape Architecture & Planning.

Because I have reasons to

conduct business there and my office is next door in the 1920s vintage Miner Building, I am quite familiar with the Quackenbush Building. I have always thought

of it as a charming blend of history and architecture. I’ve spent plenty of

time both inside and out, whether in meetings with Cameron McCarthy, perusing

the shelves of J. Michaels, or window shopping from the sidewalk.

Constructed in the so-called “Commercial

Style,” with red brick in a stretcher bond, the 2-story tall north-facing façade

on Broadway boasts ribbon windows on the upper story and large display windows

on the lower level. Two-foot-high brick walls sit beneath the display windows, which replaced original wooden panels. Overall, the Quackenbush Building’s

well-preserved original design is architecturally simple in form but skillfully

executed. Later additions on the building’s south side facing the mid-block

alley are nondescript concrete block construction possessed of far less

distinction.

Even today, walking into the

Quackenbush building is like stepping back in time. Despite the subdivision of

its first-floor level to suit the needs of its current tenants, the store’s

original spacious interior layout is evident. This is even more so within Cameron

McCarthy’s second-floor office, which encompasses the entirety of that level. The original exposed wooden posts adorned with simple capitals, tongue

& groove paneling, and built-in cabinets highlight the store's enduring

design. Studying photographs of the old store during its heyday, it is apparent

how much of its original character lives on.

One notable feature is the

rare, intact money-carrying apparatus, once a common sight in department

stores. The apparatus, with wires extending from the basement to the mezzanine

level, recalls a bygone era when intricate

systems for transferring money within the store complemented cash registers.

Due to its historic

significance and architectural quality, the Quackenbush Building is listed on

the National Register of Historic Places. Interestingly, I could find no record

of its original designer, nor who built it. My information sources for this

blog post include the building’s Wikipedia entry,

the Eugene Cultural Resource Inventory, and the National Register of Historic Places Inventory nomination form, none of which list

the architect or builder.

- The building must be of architectural interest, local importance, or historically significant.

- The building must be extant so you or I can visit it in person.

- Each building’s name will begin with a particular letter of the alphabet, and I must select one (and only one) for each of the twenty-six letters. This is easier said than done for some letters, whereas for other characters there is a surfeit of worthy candidates (so I’ll be discriminating and explain my choice in those instances).

Located at 160 E. Broadway in downtown Eugene, the Quackenbush Building stands as an all too rare surviving example of the city’s early 20th century commercial architecture.

Quackenbush Hardware Store, circa 1940 (photographer unknown; source National Park Service.gov)

Upper floor of the Quackenbush Building, home to Cameron McCarthy Landscape Architecture & Planning (photo by Visitor7, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons)

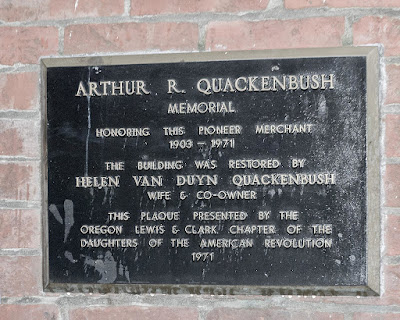

Commemorative plaque on the Quackenbush Building (photo by Visitor7, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons).

In 1969, facing urban renewal condemnation,

the store garnered support from the community. Unthank Seder Poticha

Architects accordingly determined the Quackenbush Building could be upgraded

to comply with then current building codes without adversely altering its

character; it was subsequently renovated in 1971. The old building became not

just a relic of the past but a resilient symbol of community spirit.

I’m glad citizens rallied to

save the Quackenbush Building from the wrecking ball. Along with its neighbors,

the Miner Building and the Eugene Hotel, the Quackenbush Building provides us

with a glimpse of what Eugene’s central commercial district looked like before the

urban “renewal” of the 1960s and 70s irreparably transformed the character of

the city’s downtown.

1 comment:

I thoroughly enjoyed your article and photos! In 1968 Dad used to take us kids to Quackenbushes Hardware. At that time, I remember the wooden floors squeaked, the store was packed full of inventory, lots to look at! And they had an "overhead trolly system on wires" to bring inventory to the old-timey cash register! Pretty amazing & entertaining! Miss it!!

Post a Comment